指南与共识:《中国成人2型糖尿病及糖尿病前期患者动脉粥样硬化性心血管疾病预防与管理专家共识(2023)》正式上线

2023-06-16 心血管代谢联盟 心血管代谢联盟 发表于上海

本共识旨在为心血管内科、内分泌科、肾内科和全科医学科医生提供一个较为全面的临床实践指导意见,以提高共病管理水平,改善患者心血管结局。

引言

2型糖尿病(type2 diabetes mellitus,T2DM)是动脉粥样硬化性心血管疾病(ASCVD)的主要危险因素之一,患病人数众多且增长迅速,危害巨大 。目前已知,升高的血糖可通过损伤血管促进ASCVD发生、发展和恶化。将T2DM及糖尿病前期与ASCVD进行共病管理,在确诊糖代谢异常早期即对患者进行综合干预,将有效减少 ASCVD的发生率、致死率与致残率。近年来,大量流行病学与临床干预研究结果不断公布,使我们不仅从理论上,更从实践中对这2种疾病进行共病管理成为可能 。为此,我国内分泌代谢病学、心血管病学和流行病学等多学科专家,在系统分析总结国内外心血管病和糖尿病领域最新研究进展,参考近年来国际、国内各相关领域指南与共识的基础上,发起并撰写了针对T2DM及其前期患者如何预防与管理ASCVD的共识。本共识旨在为心血管内科、内分泌科、肾内科和全科医学科医生提供一个较为全面的临床实践指导意见,以提高共病管理水平,改善患者心血管结局。

糖尿病前期和糖尿病的定义及诊断标准

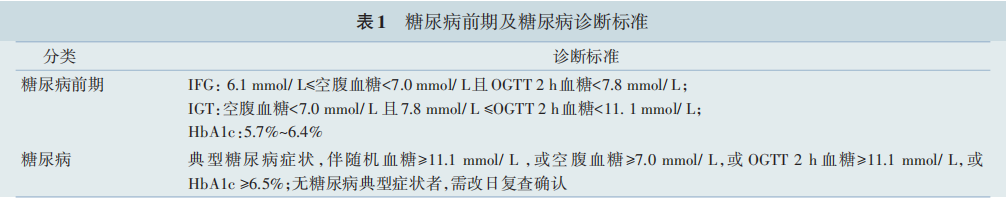

1. 糖尿病前期:糖尿病前期指葡萄糖水平不符合糖尿病标准但高于正常范围的一种血糖代谢异常状态。糖尿病前期患者是指存在空腹血糖受损(impaired fasting glucose,IFG)和/或糖耐量受损(impaired glucose tolerance,IGT),或糖化血红蛋白(glycosylated hemoglobin,HbA1c)为5.7%~6.4%的个体。诊断标准见表1。

2. 糖尿病:糖尿病是由遗传和环境因素共同引起的一组以高血糖为特征的临床综合征,其诊断标准见表1。

注:IFG,空腹血糖受损;OGTT,口服葡萄糖耐量试验;IGT,糖耐量受损;HbA1c,糖化血红蛋白 。典型糖尿病症状包括烦渴多饮、多尿、多食、不明原因体重下降和视力模糊等;随机血糖指不考虑上次用餐时间,一天中任意时间的血糖,不能用来诊断空腹血糖受损或糖耐量减低;空腹状态指至少8h没有进食热量

糖尿病前期和糖尿病的流行病学现状与疾病负担

一、我国糖尿病前期和糖尿病的流行情况

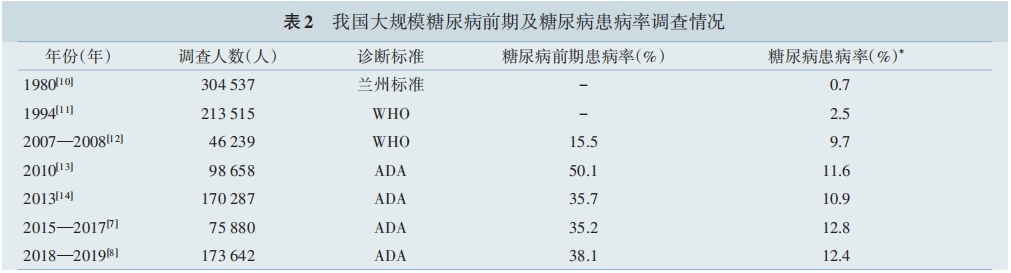

目前的全国数据显示,我国成人居民糖尿病前期年龄性别标化患病率为35.2%~38.1%,糖尿病年龄与性别标准化患病率为12.4%~12.8% 。

我国糖尿病前期和糖尿病的患病率存在年龄、性别、地区和民族的差异 。50岁及以上男性中糖尿病的加权患病率较高。31个省的糖尿病总患病率从贵州的6.2%到内蒙古的19.9%不等。不同民族糖尿病前期和糖尿病的患病率 有所差异,其中汉族糖尿病患病率最高。

近 30年来,我国糖尿病前期和糖尿病年龄标准化患病率呈增长趋势。与西方人口相比,糖尿病的知晓率、治疗率和控制率较低,中国成人患病率迅速上升(表2 )。

二、糖尿病前期和糖尿病增加我国居民的死亡 和经济负担以及心血管疾病风险

1. 糖尿病前期和糖尿病导致的死亡负担:糖尿 病前期人群的全因死亡率是非糖尿病人群的1.13 倍(95% 置信区间为 1.10~ 1.17 ) [15] 。据估计,糖尿病已成为导致中国居民死亡的第八位主要病因。1990-2016 年间,我国全年龄组糖尿病死亡率从6.3/10万上升到10.3/10万,增长了63.5%,糖尿病造成的总死亡人数增加了将近1倍。

1990-2016年我国糖尿病相关伤残调整寿命 年(disability‑adjusted life year,DALY)值从427.47万人年上升到833.73万人年 ,增加了95%,糖尿病DALY的年龄标化率从502.0/10万上升到513.7/10万,仅增加了2.3%,表明人口增长和老龄化是导致T2DM 相关 DALY 值上升的主要原因[17] 。

2. 糖尿病前期和糖尿病导致的经济负担:糖尿病的高患病率不仅影响了患者的健康状况,同时也对社会造成了严重的经济负担。调查显示,2019年,我国糖尿病相关经济负担约为1 560亿美元,占国内生产总值 (gross domestic product,GDP) 的1%[18] 。2021年,我国与糖尿病相关的医疗支出高达1 653亿美元,位居世界第二 。2025年预计可达1 700亿美元[18] 。

3. 糖尿病前期和糖尿病对心血管疾病的影响:荟萃分析研究指出,在校正了多种危险因素之后,与健康人群相比,中国糖尿病前期人群复合心血管疾病发生风险(包括冠心病和卒中等)增加11%~ 18%[15] 。中国糖尿病人群心血管疾病死亡风险是一般人群的1.90~2.26倍,研究估计中国每年约有50万例心血管疾病死亡事件可归因于糖尿病[1] 。

注:WHO,世界卫生组织;ADA,美国糖尿病学会;- 尚缺乏糖尿病前期患病率数据;* 这些大规模的糖尿病调查均没有进行糖尿病的分型诊断

糖尿病前期和2型糖尿病患者的生活方式管理

一、生活方式管理推荐建议

1. 优先选择低血糖生成指数碳水化合物(如全谷物)。增加膳食纤维摄入。用不饱和脂肪代替饱和脂肪、避免摄入反式脂肪酸。

2. 不推荐常规服用维生素或矿物质补充剂来控制血糖或改善T2DM患者的心血管风险。有微量营养素缺乏的患者,可根据营养状况适量补充。

3. 每日食盐摄入量不超过5g。

4. 不吸烟和戒烟,不饮酒或限酒(酒精量:男性< 25g/d,女性<15g/d,每周不超过2次)。

5. 每周至少应进行150min中等强度有氧运动或75min剧烈有氧运动(可组合)。

6. 推荐每日睡眠时长6~8h。

7. 推荐综合生活方式管理。

二、推荐理由

根据最新版中国居民膳食指南建议,一般人群碳水化合物的摄入推荐比例为总热量的50%~65%。进一步限制碳水化合物摄入量的饮食可能有助于T2DM人群的血糖控制,但针对T2DM人群的具体碳水化合物比例尚不明确。糖尿病前期和 T2DM 人群研究发现,健康型低碳水化合物膳食与死亡风险降低显著相关。T2DM 患者的总膳 食纤维、可溶性膳食纤维以及非可溶性膳食纤维每增加1g,卒中发生风险分别下降18%、52%和21%;总多不饱和脂肪酸、n‑3多不饱和脂肪酸和 亚油酸与总死亡风险降低显著相关,而反式脂肪和 来源于动物而非植物的单不饱和脂肪酸与较高的总死亡风险相关;补充n‑3多不饱和脂肪酸可降低T2DM患者甘油三酯和炎症因子水平。坚果摄入与T2DM患者心血管病发生和死亡风险降低显著相关。此外,大型前瞻性队列研究发现, 较高的血清维生素D水平与T2DM患者心血管和微血管并发症、痴呆以及全因死亡和心血管病死亡风险下降呈显著的剂量‑反应关系。同时,较高的血清硒水平与T2DM患者心血管病死亡以及全因死亡风险下降呈线性剂量‑反应关系,而血清叶酸和维生素B12水平与T2DM患者心血管病死亡风险呈非线性剂量‑反应关系。值得注意的是,最新的队列研究发现较高的血清β‑胡萝卜素水平与 T2DM 患者心血管病死亡风险增加显著相关。然而,目前尚缺乏能证实因果关系的临床干预研究的证据。

定期有氧运动训练与T2DM患者HbA1c水平的降低和心肺功能的提升存在关联性。 在T2DM患者和糖尿病前期人群中,吸烟与心血管病、微血管并发症、血糖控制不良、死亡风险的增加显著相关。戒烟可显著降低心血管病的发病与死亡风险 。在T2DM吸烟患者中的研究发现,相较于吸烟者,戒烟超过6年的T2DM 患者心血管并发症和全因死亡风险均显著降低,且体重变化不会影响长期戒烟的益处。睡眠时间与T2DM患者的HbA1c水平、心血管病和死亡风险呈U型关系, 睡眠时间过长(>8h)或过短(<6h)可能都不利于健康。

总体而言,在糖尿病前期和T2DM人群中,进行膳食、戒烟、限酒、定期体力活动和睡眠等多方面 的综合生活方式管理与心血管和微血管并发症、癌症和死亡风险的降低显著相关。

糖尿病前期和2型糖尿的体重管理

一、体重管理推荐建议

1. 每年至少检测一次身高、体重以计算体重指数(body mass index,BMI ),并测量腰围,评估体重变化趋势。

2. 体重管理目标:BMI≥24 kg/m2 的糖尿病前期或T2DM患者应减重,建议每天保持500~700 kcal的能量负平衡,一般将减重目标定为当前体重的10%以上。

3. 饮食管理和运动等生活方式干预是体重管理的基础。

4. 对于生活方式干预后体重仍不达标者,可进一步联合使用具有减重作用的胰高糖素样肽‑1受体(glucagon‑like peptide‑1 receptor,GLP‑1R)激动剂(限T2DM 患者)或奥利司他。

5. BMI≥32.5 kg/m2且经过非手术治疗未能达到持续减重和改善并发症效果(包括高血糖) 的T2DM患者,推荐代谢手术治疗;对BMI在27.5~ 32.4kg/m2且经过非手术治疗未达到上述效果的T2DM患者,亦可考虑将代谢手术作为一种治疗选择;对经改变生活方式和药物治疗难以控制血糖、 BMI在25.0~27.4kg/m2,且至少符合2项代谢综合征组分的T2DM患者,考虑手术治疗前需严格评估风险获益比,慎重决定。

二、推荐理由

肥胖,尤其是腹型肥胖,是 ASCVD的独立危险因素 。中国人24≤BMI<28kg/m2 为超重 ,BMI≥28kg/m2为肥胖;男性腰围≥90cm,女性腰围≥85cm为中心型肥胖(腹型肥胖)。

减重的目的不仅在于控制体重本身,更重要的是改善多重ASCVD危险因素,以减少ASCVD发病率和病死率。

减重膳食的组成原则为低能量、低脂肪、适量优质蛋白质、含复杂碳水化合物(如全谷类),增加新鲜蔬菜和水果在膳食中的比重。

奥利司他可明显改善糖尿病前期或T2DM合并肥胖患者的体重。利拉鲁肽和司美格鲁肽对糖尿病前期或T2DM合并超重、肥胖的患者具有良好的减重效果,同时可改善糖脂代谢异常。 其他口服降糖药中,二甲双胍不增加体重并有轻度的减重效果;钠‑葡萄糖协同转运蛋2 (sodium‑dependent glucose transporters 2,SGLT2)抑 制剂具有轻到中度减重效果;阿卡波糖有轻度的 减重效果[65] 。 降糖药物按照减重作用程度不同,可 分为以下几类。

(1)作用非常强:替尔泊肽、司美格 鲁肽;

(2)作用较强:利拉鲁肽;

(3)作用中等:除上述以外的GLP‑1R激动剂 、SGLT2抑制剂 、二甲双胍 ;

(4) 无影响:二肽基肽酶4 (dipeptidyl peptidase‑4,DPP‑4)抑制剂。

代谢手术在治疗肥胖T2DM及其他肥胖引起的代谢异常方面显示了独特优势。有证据表明,代谢手术治疗肥胖的T2DM患者在长期血糖、 体重控制和并发症的预防方面具有明显优势。

糖尿病前期和2型糖尿的血糖管理

一、血糖管理推荐建议

( 一 )糖尿病前期和T2DM的筛查

以空腹血糖、口服葡萄糖耐量试验及 HbA1c 检测对 T2DM 高危人群每年进行糖尿病筛查 。 高危 人群指:

( 1 )有糖尿病前期史;

(2 )年龄≥40 岁;

( 3 ) BMI≥24 kg/m2 和(或)中心型肥胖;

(4 )一级亲属有 糖尿病史;

(5)缺乏体力活动者;

(6)有巨大儿分娩 史或有妊娠期糖尿病病史的女性;

(7)有多囊卵巢 综合征病史的女性;

(8)有黑棘皮病者;

(9)有高血 压史或正在接受降压治疗者;

(10)高密度脂蛋白胆 固 醇(high density lipoprotein cholesterol,HDL‑C) < 0.90 mmol/L 和(或)甘油三酯>2.22 mmol/L,或正在接受调脂药治疗者;

(11)有 ASCVD 病史;

(12)有类 固醇类药物使用史;

(13)长期接受抗精神病药物或 抗抑郁症药物治疗;

(14)中国糖尿病风险评分总分≥ 25 分。

( 二 )糖尿病前期的T2DM预防

1. 改善生活方式是基础。

2. 二甲双胍应作为首选预防用药 。若二甲双 胍不耐受、治疗无效,或存在使用禁忌时,可考虑使 用阿卡波糖。

3. 合并冠心病的糖尿病前期人群,可考虑使用 阿卡波糖。

4. 有近期卒中病史且伴胰岛素抵抗的糖尿病 前期人群,可考虑使用吡格列酮以降低卒中和心肌 梗死风险。

(三)T2DM 的血糖管理

1. 血糖控制目标:( 1 )建议非妊娠患者HbA1c 控制在<7.0%;对于体弱者,可考虑将 HbA1c 控制 在<7.5%;对于病程较长 、预期寿命有限以及年老或体弱的成年 T2DM 患者,应考虑将 HbA1c 控制在< 8.0%。(2 )建议餐前毛细血管 血糖控制 在 4.4~ 7.0 mmol/L,餐后毛细血管血糖峰值(通常在进餐开 始后 1~2 h)控制在<10.0 mmol/L。

2. 生活方式干预是基础(详见“生活方式管理” 部分)。

3. 药物治疗:( 1 )伴有 ASCVD 或心血管疾病 (cardiovascular disease,CVD)高危人群建议优先使 用经证实有心血管获益的 GLP‑1R激动剂和(或) SGLT2 抑制剂,若同时合并心力衰竭或慢性肾脏 病 ,建 议 优 先 使 用 SGLT2 抑 制 剂 ;( 2 )对 于 没 有 GLP‑1R 激动剂和(或)SGLT2抑制剂强适应证的 T2DM 患者,二甲双胍可以作为常规的一线降糖药 物;(3 )二甲双胍与GLP‑1R激动剂、SGLT2 抑制剂 联合使用是合理的;(4 )其他降糖药物可根据血糖 控制的需求个体化地应用;(5)如果患者处于严重 高 血 糖 状 态 ( 如 HbA1c>10% 或 血 糖 水 平 > 16.7 mmol/L,伴有明显高血糖相关症状)或明显分 解代谢状态(体重明显减轻),则应考虑启用胰岛素 治疗。

二、推荐理由

对糖尿病前期患者进行生活方式干预可以显 著延缓甚至逆转其进展为 T2DM 的进程并减少远期全因死亡和心血管相关死亡[ 73 ] 。二甲双胍和阿 卡 波 糖 可 以 显 著 延 缓 糖 尿 病 前 期 进 展 为 T2DM。 小规模研究显示,二甲双胍可以减少 糖尿病前期合并稳定期 ASCVD 患者的复合心血管 事件风险。

GLP‑1R激动剂能够减少 T2DM 患者 ASCVD 心 血 管 事 件 风 险(包 括 非 致 死 性 心 肌 梗 死 和 卒 中 等 ) [ 78‑80] 。SGLT2 抑 制 剂 可 以 减 少 心 血 管 高 危 T2DM 患 者 主 要 不 良 心 血 管 事 件(major adverse cardiovascular events,MACE)和 心 血 管 死 亡 的 发 生,特别是在合并 ASCVD 的 T2DM 患者中作用更 明显[ 3‑4,79] 。此外,SGLT2 抑制剂对于心力衰竭患者 预后的改善和对肾脏的保护作用已得到多个随机 对照临床研究结果的证实。

二甲双胍使新诊断、不伴心血管疾病但超重或 肥胖的 T2DM 患者心肌梗死事件发生率减少 39%, 冠状动脉死亡减少 50%,卒中发生率减少 41%。

吡格列酮降低糖尿病前期患者发展为 T2DM 的风险。对糖尿病前期和 T2DM 患者,吡格列酮 延缓动脉粥样硬化进展[86] ,减少心肌梗死和卒中风 险,但未减少全因死亡率,且增加水肿、体重上升、 骨折和心力衰竭的发生风险

糖尿病前期和2型糖尿患者的血压管理

一、血压管理推荐建议

( 一 )危险分层

对糖尿病前期、T2DM 合并高血压患者进行心 血管风险分层,需综合考虑其他心血管危险因素、 靶器官损害和临床并发症,具体分层方法详见《中 国高血压防治指南(2018 年修订版) 》 。

( 二 )降压目标

1. 对于合并高血压患者,应根据患者实际情 况,个体化确定患者的血压目标:糖尿病前期合并 高血压患者推荐血压控制目标为 <140/90 mmHg ( 1 mmHg=0. 133 kPa);能耐受者 、伴有微量白蛋白 尿者 和 部 分 高 危 及 以 上 的 患 者 可 进 一 步 降 至< 130/80 mmHg 。T2DM 合并高血压的患者,推荐血 压控制目标为<130/80 mmHg。

2. 糖尿病合并妊娠者,建议血压控制目标为 ≤ 135/85 mmHg。

(三)降压方案

1. 对于糖尿病前期合并高血压的中危患者,在 改善生活方式的基础上,血压仍≥140/90 mmHg 时, 应启动药物治疗。

2. 对于糖尿病前期合并高血压的高危和极高危患者,立即启动降压治疗。

3. T2DM 合并血压持续≥130/80 mmHg 的患者, 在能耐受的情况下,可将血压降至低于此水平。

4. 降压药物的选择:( 1 )推荐起始使用肾素‑血管紧张素‑醛固酮系统 (renin‑angiotensin‑ aldosterone system,RAAS)阻滞剂[血管紧张素转化 酶 抑 制 剂/血 管 紧 张 素 受 体 拮 抗 剂( angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor , ACEI / angiotensin receptor blocker,ARB )或血管紧张素受体脑啡肽酶 抑 制 剂 ( angiotensin receptor‑neprilysin inhibitor, ARNI )]用于治疗T2DM合并高血压,尤其是伴有微 量白蛋白尿、白蛋白尿、慢性肾脏病(chronic kidney diseae,CKD)、左心室肥大、冠心病及心力衰竭时。 ( 2 )当诊室血压≥160/100 mmHg 或高于目标血压 20/10 mmHg 及以上,以及高危患者或单药未达标 的患者,应启动 2 种降压药物的联合方案 。优先推荐 RAAS 阻滞剂联合钙通道阻滞剂或者利尿剂降压,对伴有心率增快(静息心率>80 次/min)或者合 并冠心病和心力衰竭者,可考虑加用 β 受体阻滞 剂 。在 2 种药物联合方案中,优先推荐单片固定复 方制剂。(3 )如血压仍不能控制达标,可考虑三联药 物 治 疗 ,最 佳 的 三 药 联 合 方 案 为 RAAS 阻 滞 剂 ( ARNI 或 ACEI/ARB)+钙通道阻滞剂+利尿剂。(4 ) 如已使用 3 种药物进行联合降压治疗后血压仍难 以控制,可加用盐皮质激素受体拮抗剂或 α 受体阻 滞剂,并应筛查继发性高血压,同时需评估降压药 物治疗方案的合理性(药物的种类与剂量)及患者 服药依从性。

5. 对于无明确心血管并发症的糖尿病前期患 者,若无明确交感神经激活的表现(如静息心率> 80 次/min),慎用β 受体阻滞剂或噻嗪类利尿剂。

6. 使用 RAAS 阻滞剂(ARNI 或 ACEI/ARB)时, 应当监测血钾水平和肾小球滤过率。

二、推荐理由

T2DM 和糖尿病前期患者中高血压的患病率 高于血糖正常人群,高血压在 T2DM、糖尿病前期 和血糖正常人群中的患病率分别为 55.5%、36.6%和 25.0%,我国门诊就诊的 T2DM 患者中约 30% 伴有高血压。

研究显示,在糖尿病前期人群强化降压(收缩 压<120 mmHg)较常规降压(收缩压<140 mmHg)可 进一步减少复合心血管事件的发生,但显著增加 T2DM 的危险和空腹血糖异常发生率。但在基 线血压≥140/90 mmHg 的T2DM 患者中,降压治疗能 够减少心血管复合终点事件(非致死性心肌梗死、 非致死性卒中、心血管死亡)及延缓蛋白尿和视网 膜病变的发生发展;强化降压(收缩压<120 mmHg) 较常规降压(收缩压<140 mmHg)没有进一步减少 T2DM 患者 MACE 风险[94‑95] 。近期研究表明,T2DM 合并高血压患者的降压幅度与心血管事件发生呈 U 型曲线,血压<120/70 mmHg 时心血管事件风险 显著增加。

不同类型降压药对糖代谢影响不同:RAAS 阻 滞剂有可能减少新发糖尿病风险,而阿替洛尔等 β 受体阻滞剂或噻嗪类利尿剂可能增加新发糖尿病 风险,钙通道阻滞剂对新发糖尿病风险无影响。 对于同时合并冠心病的患者,建议使用 β 受体阻滞 剂;合并心力衰竭者,可以根据需要使用利尿剂。

在 T2DM 伴 高 血 压 患 者 中 ,ARNI 较 ACEI 或 ARB 能更有效地改善心脏重构、减轻蛋白尿;对于 合并 ASCVD 或尿白蛋白肌酐比值(urine albumin‑ to‑creatinine ratio,UACR)>30 mg/g 的T2DM 伴高血 压患者,RAAS 阻滞剂可显著减少心血管事件、延 缓肾病进展。

糖尿病前期和2型糖尿患者的血脂管理

T2DM 患 者 血 脂 异 常 的 发 生 率 明 显 高 于 非 T2DM 患者,其主要表现为增高的甘油三酯、轻度升高的低密度脂 蛋白胆固醇 (low density lipoprotein cholesterol,LDL‑C) ,含 载 脂 蛋 白 B(apolipoprotein B,apoB)残粒升高 ,以及低 HDL‑C 水平 [ 102 ] 。

一、胆固醇管理

( 一 )胆固醇管理推荐建议

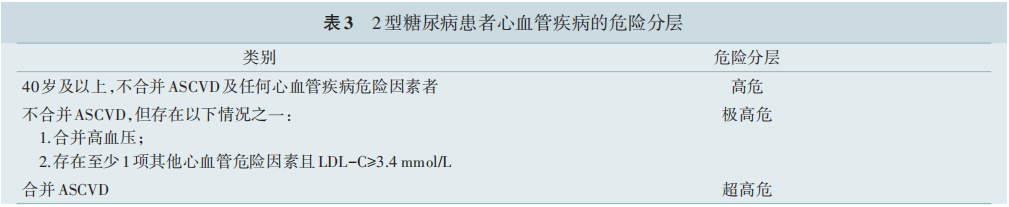

1. 糖尿病前期和 T2DM 患者心血管疾病的危 险分层:( 1 ) 由于糖尿病前期仅轻度增加 CVD 风 险,糖尿病前期人群参照普通人群进行危险分层 [详见《中国胆固醇教育计划调脂治疗降低心血管 事件专家建议(2019)》];( 2 )根据T2DM 病程长 短、是否合并 ASCVD 及主要靶器官损害,将 T2DM 患 者 分 为 高 危 、极 高 危 和 超 高 危 组 。 分 类 方 法 见表 3。

2. 糖尿病前期和 T2DM 患者 LDL‑C 控制目标: ( 1 )建议糖尿病前期和T2DM 患者根据心血管疾病 危险分层确定 LDL‑C 控制目标值;(2 )对于低危患 者,LDL‑C 控制目标为<3.4 mmol/L;(3 )对于中/高 危患者,LDL‑C 控制目标为<2.6 mmol/L;(4 )对于极 高危患者,LDL‑C 控制目标为<1.8 mmol/L 且较治疗 前降幅>50%;(5)对于超高危患者,建议 LDL‑C 尽 快降至<1.4 mmol/L 且较治疗前降幅>50%。

3. 糖尿病前期和 T2DM 患者的降胆固醇治疗 方案:( 1 )推荐40 岁及以上的 T2DM 患者,无论基线 胆固醇水平如何,均使用他汀类药物进行 ASCVD 一级预防;(2 )中等强度他汀类药物应作为降胆固 醇治疗的基础用药;(3 )单用他汀类药物治疗后 LDL‑C 不达标者,建议联用胆固醇吸收抑制剂和 (或) 前 蛋 白 转 化 酶 枯 草 溶 菌 素/kexin 9 型 (proprotein convertase subtilisin / kexin type 9, PCSK9)抑制剂;(4)他汀类药物不耐受者,建议使用胆固醇吸收抑制剂和(或)PCSK9 抑制剂;(5)他汀类药物禁用于妊娠期妇女。

( 二 )推荐理由

LDL‑C 是糖代谢异常患者调脂治疗的首要干预靶点,其控制目标值由心血管危险分层决定 。对 于中危或高危患者,将 LDL‑C 降至 2.6 mmol/L 以下 可显著降低心血管事件风险或全因死亡率。 对于极高危患者,LDL‑C 降至 1.4 mmol/L 以下能进 一步降低心血管事件风险。对于 2 年内再发 主要心血管事件的超高危患者,可考虑将 LDL‑C< 1.0 mmol / L 作 为 目 标 值 且 降 幅 较 治 疗 前 > 50%。

他汀类药物是降低 LDL‑C 的一线用药,能显著 降低 T2DM 患者的复合心血管事件和血运重建风险。 尽 管 他 汀 类 药 物 可 轻 度 增 加 T2DM 风 险,但心血管净获益显著。

胆固醇吸收抑制剂和 PCSK9 抑制剂经由不同 途径降低 LDL‑C,均具有明确的心血管获益,可作 为他汀类降脂药的有效补充 。研究显示:( 1 )在他 汀类药物治疗的基础上,加用依折麦布可以降低 T2DM 合并 ASCVD 患者24% 心肌梗死风险和39% 缺血性卒中风险;( 2 )对于他汀类药物联合依折 麦布治疗后血脂仍不达标的极高危 ASCVD 患者 ( T2DM 占比约 30%),PCSK9 抑制剂在进一步降低 LDL‑C 的 同 时 更 显 著 降 低 心 血 管 事 件 风 险,且不增加新发 T2DM 风险;( 3 )与 糖代谢正常或糖尿病前期合并急性冠状动脉综合 征(acute coronary syndrome,ACS)患者相比,在他汀 类药物治疗的基础上,短期联合 PCSK9 抑制剂强化 降脂能使 T2DM 合并 ACS 患者心血管不良事件风 险的绝对降幅更大;( 4 )在他汀类药物治疗的基 础上联合 PCSK9 抑制剂能让合并T2DM 的 ASCVD 患者(包括陈旧性心肌梗死、缺血性卒中、有症状的 外 周 血 管 疾 病 )较 非 T2DM 患 者 产 生 更 大 的 获 益;(5)早期使用他汀类药物联合 PCSK9 抑制剂 的强化降脂治疗带来的保护作用可以长时间存在, 且不增加糖代谢异常的风险。

作用于 PCSK9 位点的药物还包括小干扰 RNA 制剂 Inclisiran,其可靶向肝脏降解 PCSK9 mRNA, 进而减少其蛋白合成 。 全球大型 3 期临床研究 ORION‑9、ORION‑10、ORION‑11 结果显示,每半年 注射一次 Inclisiran 可长久平稳地降低LDL‑C 水平, 降 幅 达 到 50%~55%,且 总 体 安 全 耐 受 性 良 好 。相较于目前的 PCSK9 抑制剂,Inclisiran 可显著 提 高 患 者 依从性。 探 索 性 终 点 分 析 显 示 Inclisiran 降 低 25% 的 心 血 管 复 合 终 点 事 件风险。

二、甘油三酯管理

( 一 )推荐建议

1. 对于轻‑中度高甘油三酯血症患者,推荐控 制生活方式相关因素(肥胖和代谢综合征)和其他 影响因素(T2DM、慢性肝病、慢性肾病、肾病综合征 和甲状腺功能降低)。

2. 对于重度高甘油三酯血症患者,建议筛查导 致甘油三酯升高的可能影响因素并予以降甘油三 酯药物(如贝特类)治疗以降低胰腺炎风险。

3. 对于合并 ASCVD 或者心血管危险因素且他 汀治疗后 LDL‑C 达标的高甘油三酯患者,可考虑加 用二十碳五烯酸乙酯以进一步降低心血管疾病 风险。

( 二 )推荐理由

甘油三酯升高也会增加心血管事件风险。 对于 T2DM 患者高甘油三酯的管理,建议以改善生 活方式为主,包括清淡和低糖饮食、加强体育锻炼、 减重和戒酒等。 对于轻‑中度高甘油三酯血 症患者(空腹甘油三酯 2.30~5.65 mmol/L),他汀类 药物仍然是降脂治疗的首选。对于中度高甘油 三酯血症合并 ASCVD 或者T2DM 伴至少一种其他 心血管危险因素的患者,在他汀类药物治疗的基础 上加用二十碳五烯酸乙酯可进一步降低心血管复 合终点事件风险。对于在他汀类药物治疗的基 础上,联合贝特类药物是否进一步有心血管获益仍 无一致结论,有待于进一步研究。

三、脂蛋白(a)管理

( 一 )推荐建议

1. 成年人终 生 至 少 检 测 一 次 脂 蛋 白 (a) [lipoprotein(a),Lp (a)]水平。

2. Lp (a)水平与ASCVD 疾病风险具有正相关 性,对于中国患者,Lp(a)>30 mg/dl 者 ASCVD 风险 显著增加。

3. 对于 Lp(a)升高的患者 ,强化生活方式干 预、LDL‑C 及其他危险因素控制是基础。

( 二 )推荐理由

Lp (a)水平高低与遗传因素密切相关(遗传因 素影响占比>90%)。 而 T2DM 患者 Lp (a)水平与 ASCVD 风险呈正相关 。 反义寡核苷酸药物 Pelacarsen 通过靶向作用于载脂蛋白a 的mRNA,抑 制其转化为蛋白质,使 Lp(a)降低70%~90%,总体安全性良好,以心血管事件为终点的三期临床试验正在进行。

注:ASCVD,动脉粥样硬化性心血管疾病;LDL-C,低密度脂蛋白胆固醇 。其他心血管危险因素包括年龄(男性≥45 岁或女性≥55 岁)、吸 烟、高密度脂蛋白胆固醇低、体重指数≥28 kg/m2、早发缺血性心血管病家族史

糖尿病前期和2型糖尿患者的抗血小板药物治疗

一、抗血小板药物使用的推荐建议

1. 对于 ASCVD 高危患者,需在全面评估获益 和出血风险的基础上谨慎考虑阿司匹林的使用,不 推荐阿司匹林用于 40 岁以下和 70 岁以上患者的一 级预防。

2. 无充分证据表明将 P2Y12 受体拮抗剂、吲哚布芬、西洛他唑及双嘧达莫用于 T2DM 患者 ASCVD 的一级预防有显著的临床净获益。

3. 建议小剂量阿司匹林(75~ 100 mg/d)用于 ASCVD 合并T2DM 患者的二级预防,若不耐受则使 用氯吡格雷、替格瑞洛、吲哚布芬或西洛他唑(经皮 冠状动脉介入治疗术后)替代。

4. 在 急 性 冠 状 动 脉 综 合 征 (acute conoary syndrome,ACS)或者冠状动脉支架置入术后 1 年内 的患者使用双联抗血小板治疗(低剂量阿司匹林和 P2Y12 受体抑制剂)是合理的。

5. 对于既往有冠状动脉介入治疗史且存在高 缺血和低出血风险的 T2DM 合并慢性冠状动脉综 合征患者,可考虑长期双联抗血小板治疗。

6. 对于稳定性冠心病和(或)外周动脉疾病且 出血风险低的患者,可考虑采用阿司匹林联合低剂 量利伐沙班,以预防肢体和脑血管事件。

二、推荐理由

T2DM 患者采用阿司匹林一级预防可显著降 低严重血管事件的风险,但同时出血风险也增加, 其绝对获益大部分被出血风险抵消。荟萃分析显示,对于 T2DM 患者,阿司匹林一级预防显著增 加大出血风险。

阿司匹林对 ASCVD 的二级预防作用已经非常 明确。对于 ACS 且已行冠状动脉支架置入术的 T2DM 患者,在阿司匹林治疗基础上,联合普拉格 雷较氯吡格雷降低 30% MACE 发生率,且不增 加大出血的发生率 。 同时,既往发生心肌梗死的 T2DM 患者中,阿司匹林联合替格瑞洛较阿司匹林 单药显著降低心血管事件风险、心血管死亡率和冠 心病死亡率。值得注意的是,在合并稳定性冠心病的 T2DM 患者中,延长双联抗血小板治疗时间 虽然减少缺血事件发生率,但显著增加包括颅内出 血在内的大出血的发生。 因此,双联抗血小 板治疗不推荐用于出血风险高的 T2DM 合并稳定 性冠心病患者 。对于经皮冠状动脉介入治疗术后 服用(12±6)个月双联抗血小板治疗且未出现心血 管事件的患者,继续长期使用氯吡格雷单药治疗较 阿司匹林单药治疗的心血管事件发生率更低、出血事件发生率也更低,提示长期氯吡格雷单药治疗可能带来更多临床获益。 阿司匹林联合低剂量利伐沙班较阿司匹林单药显著减少 T2DM 合并稳定 性冠心病或外周动脉疾病患者 MACE,此获益主要来源于全因死亡、脑血管事件和肢体血管事件的减少。

2型糖尿病合并动脉粥样硬化性心血管疾病患者的并发症与合并症管理

一、慢性肾脏病管理

( 一 )慢性肾脏病管理的推荐建议

1. 对于糖尿病前期或 T2DM 合并 CKD 的患者,优先选择具有肾脏获益的药物,同时监测估算肾小球滤过率 ( estimated glomerular filtration rate, eGFR)、UACR 和血钾水平,并据此调整药物种类和 剂量。

2. 降糖药物中,优先推荐 SGLT2抑制剂以延缓 肾病进展[ 当 eGFR≥20 ml ·( min · 1.73m2 ) ‑1 时],当存在 SGLT2抑制剂使用禁忌或不能耐受时,推荐给予有心血管获益的 GLP‑1R激动剂。

3. T2DM合并 CKD 的患者推荐使用RAAS 抑制 剂(ACEI/ARB、ARNI )治疗,治疗过程中出现血肌 酐升高>30% 时应暂停药物使用。

4. 为了改善心血管和肾脏结局,在合并蛋白尿 且 eGFR≥25 ml ·( min · 1.73 m2 ) ‑1 时可考虑使用非奈 利酮治疗,治疗前后需监测血钾变化。

( 二 )推荐理由

SGLT2 抑制剂可改善 T2DM 合并肾脏病患者 的预后[ 147 ] ,这种作用独立于其降糖效应存在,与其 降低血压、减轻体重、减低肾小球囊内压、减少蛋白尿 、延 缓 肾 小 球 滤 过 率(glomerular filtration rate, GFR)下降密切相关 。GLP‑1R激动剂也具有直接 的肾脏保护作用,可改善肾脏预后[ 80,148‑150] 。

RAAS 抑制剂是T2DM合并 CKD 患者的基础治 疗,尤其对于同时合并高血压的患者,可进一步延 缓蛋白尿的进展 。 同时,非甾体选择性盐皮质激素 受体拮抗剂非奈利酮可显著延缓伴有蛋白尿的 CKD 进展并降低心血管终点事件风险[151‑155] 。

二、糖尿病视网膜病变管理

( 一 )糖尿病视网膜病变管理的推荐建议

1. 对无视网膜病变且血糖控制良好的 T2DM 患者,每年进行一次视网膜检查 。若存在视网膜病 变,则视情况增加检查频率。

2. 强化 T2DM 患者血糖、血压和血脂的综合管 理,积极改善患者微循环功能障碍,可预防或延缓 T2DM 患者视网膜病变进展 、缓解症状,但是已经 有较重病变者不宜强化降糖。

3. 对于合并高甘油三酯血症的患者,使用非诺贝特可延缓视网膜病变进展。

4. 推荐玻璃体腔注射抗血管内皮生长因子 (vascular endothelial growth factor,VEGF)抑制剂作 为损伤视力的视网膜黄斑水肿的一线治疗,也可用 于一部分视网膜增殖性病变患者以替代光凝疗法。 玻璃体内激素治疗可以作为第二选择。

( 二 )推荐理由

虽然强化降糖可以预防视网膜病变的发生,但是对于已经有非增殖性中度以上病变患者会加重 视网膜病变甚至失明,因此较重病变者不宜强化降 糖。对于合并高血压的患者,降压治疗可以减 少糖尿病视网膜病变进展,但强化降压并没有带来 进一步获益。非诺贝特可以延缓高甘油三酯血 症患者的糖尿病视网膜病变进展,尤其是非增殖性 糖尿病视网膜病变。 目前,通过改善微循环 来防治糖尿病视网膜病变是一个活跃的领域,多项 临床研究正在进行,已完成的研究提示复方丹参滴丸可以延缓病情进展并改善症状。

玻璃体内注射抗 VEGF 抑制剂对延缓增殖性 糖尿病性视网膜病变有效,对黄斑中心受累型糖尿 病黄斑水肿的作用优于激光单一疗法;在视力保护 方面不劣于全视网膜激光光凝治疗。

皮质类固醇可通过多种机制产生抗炎作用,帮 助修复视网膜屏障并减少渗出。

三、心力衰竭管理

( 一 )心力衰竭推荐建议

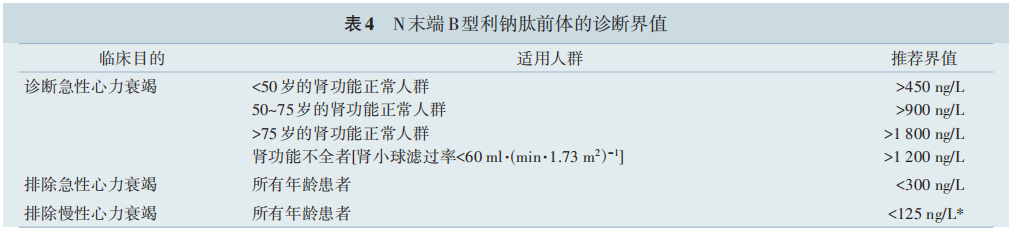

1. 对于没有症状或者症状不典型的心力衰竭 高危人群,推荐每年进行心脏超声和脑钠肽/N 末端 B 型 利 钠 肽 前 体 (brain natriuretic peptide,BNP / N‑terminal pro‑B‑type natriuretic peptide,NT‑proBNP) 检 测 (诊 断 界 值 见 表 4 ),以 筛 查 早 期 心 力 衰 竭 患者。

2. 推荐使用 SGLT2 抑制剂以减少心力衰竭的 发病及住院风险。

3. 合并射血分数下降的心力衰竭(heart failure with reduced ejection fraction,HFrEF )患者推荐联合 使用 RAAS 抑制剂(优先使用ARNI 或以 ARNI替换 ACEI/ARB)、有证据的 β 受体阻滞剂和盐皮质受体 拮抗剂(非奈利酮优先)。

4. 合 并 射 血 分 数 中 间 值 的 心 力 衰 竭 (heart failure with mid‑range ejection fraction,HFmrEF )患 者必要时可联合使用 ARNI/ACEI/ARB,盐皮质受 体拮抗剂和 β 受体阻滞剂。

5. 合并射血分数保留心力衰竭(heart failure with preserved ejection fraction,HFpEF)患者必要时 可联合使用盐皮质受体拮抗剂和 ARNI。

6. 不建议在心力衰竭患者中使用噻唑烷二酮 类药物(包括吡格列酮和罗格列酮)。

( 二 )推荐理由

对于糖尿病前期或 T2DM 合并 HFrEF 的患者, RAAS 抑制剂、β 受体阻滞剂、盐皮质激素受体拮抗剂和 SGLT2抑制剂均可改善心血管死亡和心力衰 竭住院风险。SGLT2 抑制剂可减少 HFpEF 患 者的心血管复合终点事件风险、心力衰竭发生和心 力衰竭恶化。ARNI 可改善 HErEF 合并糖 尿病前期患者(心力衰竭住院、心血管死亡和全因 死亡)及 T2DM 患者(心力衰竭住院)的预后,非 奈利酮可减少合并 CKD 的 T2DM 患者的心力衰竭 住院风险。 噻唑烷二酮类药物(包括吡格列酮 和 罗 格 列 酮 ) 可 增 加 水 钠 潴 留 和 心 力 衰 竭 风险。

四、阻塞性睡眠呼吸暂停管理

( 一 )阻塞性睡眠呼吸暂停管理推荐建议

1. 存在阻塞性睡眠呼吸暂停相关症状(如打鼾、白天睡眠时间延长、有呼吸暂停表现等)的 T2DM患者应积极进行筛查。

2. 推荐积极治疗睡眠呼吸暂停(包括改善生活 方式 、持续性正压通气 、佩戴口腔矫治器和手术 等),可明显提高生活质量、改善高血压。

( 二 )推荐理由

在 T2DM 患者中,阻塞性睡眠呼吸暂停的发生 率可能高达 23%。其诊断依赖于睡眠监测 。积极治疗睡眠呼吸暂停对于血糖的调节作用尚无定论。

五、非酒精性脂肪性肝病管理

( 一 )非酒精性脂肪性肝病管理推荐建议

1. T2DM 患者应该筛查非酒精性脂肪性肝病 (nonalcoholic fatty liver disease,NAFLD),特别是超 重肥胖的患者。

2. T2DM 合并 NAFLD 的患者如果有治疗 NAFLD 需要时可选吡格列酮或利拉鲁肽。

( 二 )推荐理由

NAFLD 包括单纯性脂肪肝 、非酒精性脂肪性肝炎、肝纤维化、肝硬化,少数可以发展为肝癌。 因为检查技术和方法不同,文献中报道的 T2DM 人群中 NAFLD 患 病 率 差 异 大 (50%~80%) 。NAFLD 是 ASCVD 的 高 危 因 素 ,CVD 是 其 首 要 死 因,并与其肝脏病变严重程度无关。要重视糖 尿病前期及 T2DM 人群 NAFLD 的早筛、早诊和早期干预。T2DM 患者合并 NAFLD 时,除了防治 ASCVD,还须重视肝脏病变(包括肝纤维化 、肝硬化和肝癌等)的定期监测和防治,对活动性肝脏炎症进行专科干预是必要的 。在降糖药中,吡格列酮具有抗动脉粥样硬化且抑制肝纤维化进展作用。同时,有研究指出,利拉鲁肽有潜在的减少肝脏内脂肪和肝纤维化作用,尤其对于肥胖患者。

注:*敏感度和特异度较低

小结

综上所述,本共识回顾了糖尿病前期和T2DM与ASCVD的流行病学现状,对生活方式、体重、血糖、血压和血脂等因素的管理、抗血小板药物的应用、常见合并症的管理给出了详细的推荐建议。希望本共识可以给心血管内科、内分泌科、肾内科和全科医学科医生提供一个较为全面的临床实践指导意见,以提高共病管理水平,改善患者心血管健康与结局。

参考文献:

[1] Bragg F, Li L, Yang L, et al. Risks and population burden of cardiovascular diseases associated with diabetes in China: a prospective study of 0.5 million adults[J]. PLoS Med,2016,13 (7):e1002026. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002026.

[2] Effect of intensive bloodglucose control with metformin on complications in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 34). UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group[J]. Lancet, 1998,352(9131):854865.

[3] Kosiborod M, Lam C, Kohsaka S, et al. Cardiovascular events associated with SGLT2 inhibitors versus other glucoselowering drugs: the CVDREAL 2 study[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2018, 71(23): 26282639. DOI: 10.1016 / j. jacc.2018.03.009.

[4] Gliflozins in the Management of Cardiovascular Disease[J]. N Engl J Med, 2022, 387(13): 1244. DOI: 10.1056 / NEJMx220008.

[5] ÁlvarezVillalobos NA, TreviñoAlvarez AM, González González JG. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2diabetes[J]. N Engl J Med, 2016,375(18):17971798.DOI: 10.1056/NEJMc1611289.

[6] Marso SP, Bain SC, Consoli A, et al. Semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes[J]. N Engl J Med, 2016, 375(19): 18341844. DOI: 10.1056 / NEJMoa1607141.

[7] Li Y, Teng D, Shi X, et al. Prevalence of diabetes recorded in mainland of China using 2018 diagnostic criteria from the American Diabetes Association: national cross pal study[J]. BMJ, 2020,369:m997. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.m997.

[8] Wang L, Peng W, Zhao Z, et al. Prevalence and treatment of diabetes in China, 20132018[J]. JAMA, 2021, 326(24): 24982506. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2021.22208.

[9] Li Y, Guo C, Cao Y. Secular incidence trends and effect of population aging on mortality due to type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus in China from 1990 to 2019: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019[J]. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care, 2021, 9(2): e002529. DOI: 10.1136 / bmjdrc2021002529.

[10] 钟学礼 . 全国 14 省市 30 万人口中糖尿病调查报告 [J]. 中 华内科杂志,1981,20(11): 678683.

[11] Pan XR, Yang WY, Li GW, et al. Prevalence of diabetes and its risk factors in China, 1994. National Diabetes Prevention and Control Cooperative Group[J]. Diabetes Care, 1997, 20 (11):16641669. DOI: 10.2337/diacare.20.11.1664.

[12] Yang W, Lu J, Weng J, et al. Prevalence of diabetes among men and women in China[J]. N Engl J Med, 2010, 362(12): 10901101. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908292.

[13] Xu Y, Wang L, He J, et al. Prevalence and control of diabetes in Chinese adults[J]. JAMA, 2013, 310(9): 948959. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2013.168118.

[14] Wang L, Gao P, Zhang M, et al. Prevalence and ethnic pattern of diabetes and prediabetes in China in 2013[J]. JAMA, 2017, 317(24): 25152523. DOI: 10.1001 / jama.2017.7596.

[15] Cai X, Zhang Y, Li M, et al. Association between prediabetes and risk of all cause mortality and cardiovascular disease: updated metaanalysis[J]. BMJ, 2020, 370: m2297. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.m2297.

[16] Zhou M, Wang H, Zeng X, et al. Mortality, morbidity, and risk factors in China and its provinces, 19902017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017[J]. Lancet, 2019,394(10204):11451158. DOI: 10.1016/ S01406736(19)304271.

[17] Liu M, Liu SW, Wang LJ, et al. Burden of diabetes, hyperglycaemia in China from to 2016: findings from the 1990 to 2016, global burden of disease study[J]. Diabetes Metab, 2019, 45(3): 286293. DOI: 10.1016 / j. diabet.2018.08.008.

[18] Zhu D, Zhou D, Li N, et al. Predicting diabetes and estimating its economic burden in china using autoregressive integrated moving average model[J]. Int J Public Health, 2021,66:1604449. DOI: 10.3389/ijph.2021.1604449.

[19] Sainsbury E, Kizirian NV, Partridge SR, et al. Effect of dietary carbohydrate restriction on glycemic control in adults with diabetes: a systematic review and metaanalysis[J]. Diabetes Res Clin Pract, 2018,139:239252. DOI: 10.1016/j. diabres.2018.02.026.

[20] Li L, Shan Z, Wan Z, et al. Associations of lowercarbohydrate and lowerfat diets with mortality amongpeople with prediabetes[J]. Am J Clin Nutr, 2022, 116(1): 206215. DOI: 10.1093/ajcn/nqac058.

[21] Wan Z, Shan Z, Geng T, et al. Associations of moderate lowcarbohydrate diets with mortality among patients with type 2 diabetes: a prospective cohort study[J]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2022,107(7):e2702e2709. DOI: 10.1210/ clinem/dgac235.

[22] Tanaka S, Yoshimura Y, Kamada C, et al. Intakes of dietary fiber, vegetables, and fruits and incidence of cardiovascular disease in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes[J]. Diabetes Care, 2013,36(12):39163922. DOI: 10.2337/dc130654.

[23] Jiao J, Liu G, Shin HJ, et al. Dietary fats and mortality among patients with type 2 diabetes: analysis in two population based cohort studies[J]. BMJ, 2019, 366: l4009. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.l4009.

[24] GuaschFerré M, Babio N, MartínezGonzález MA, et al. Dietary fat intake and risk of cardiovascular disease and allcause mortality in a population at high risk of cardiovascular disease[J]. Am J Clin Nutr, 2015, 102(6): 15631573. DOI: 10.3945/ajcn.115.116046.

[25] Hendrich S. (n3) fatty acids: clinical trials in people with type 2 diabetes[J]. Adv Nutr, 2010, 1(1): 37. DOI: 10.3945 / an.110.1003.

[26] De Luis DA, Conde R, Aller R, et al. Effect of omega3 fatty acids on cardiovascular risk factors in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertriglyceridemia: an open study[J]. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci, 2009,13(1):5155.

[27] Tajuddin N, Shaikh A, Hassan A. Prescription omega3 fatty acid products: considerations for patients with diabetes mellitus[J]. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes, 2016, 9: 109118. DOI: 10.2147/DMSO.S97036.

[28] Liu G, GuaschFerré M, Hu Y, et al. Nut consumption in relation to cardiovascular disease incidence and mortality among patients with diabetes mellitus[J]. Circ Res, 2019,124 (6):920929. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.314316.

[29] Wan Z, Guo J, Pan A, et al. Association of serum 25hydroxyvitamin D concentrations with allcause and causespecific mortality among individuals with diabetes[J]. Diabetes Care, 2021, 44(2): 350357. DOI: 10.2337 / dc201485.

[30] Lu Q, Wan Z, Guo J, et al. Association between serum 25hydroxyvitamin D concentrations and mortality among adults with prediabetes[J]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2021, 106(10):e4039e4048. DOI: 10.1210/clinem/dgab402.

[31] Chen X, Wan Z, Geng T, et al. Vitamin D status, vitamin D receptor polymorphisms, and risk of microvascular complications among individuals with type 2 diabetes: a prospective study[J]. Diabetes Care, 2023, 46(2): 270277. DOI: 10.2337/dc220513.

[32] Wan Z, Geng T, Li R, et al. Vitamin D status, genetic factors, and risk of cardiovascular disease among individuals with type 2 diabetes: a prospective study[J]. Am J Clin Nutr, 2022 [Online ahead of print]. DOI: 10.1093/ajcn/nqac183.

[33] Geng T, Lu Q, Wan Z, et al. Association of serum 25hydroxyvitamin D concentrations with risk of dementia among individuals with type 2 diabetes: a cohort study in the UK Biobank[J]. PLoS Med, 2022, 19(1): e1003906. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003906.

[34] Qiu Z, Geng T, Wan Z, et al. Serum selenium concentrations and risk of allcause and heart disease mortality among individuals with type 2 diabetes[J]. Am J Clin Nutr, 2022,115 (1):5360. DOI: 10.1093/ajcn/nqab241.

[35] Liu Y, Geng T, Wan Z, et al. Associations of serum folate and vitamin B12 levels with cardiovascular disease mortality among patients with type 2 diabetes[J]. JAMA Netw Open, 2022, 5(1): e2146124. DOI: 10.1001 / jamanetworkopen.2021.46124.

[36] Qiu Z, Chen X, Geng T, et al. Associations of serum carotenoids with risk of cardiovascular mortality among individuals with type 2 diabetes: results from NHANES[J]. Diabetes Care, 2022, 45(6): 14531461. DOI: 10.2337 / dc212371.

[37] Boulé NG, Haddad E, Kenny GP, et al. Effects of exercise on glycemic control and body mass in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a metaanalysis of controlled clinical trials[J]. JAMA, 2001, 286(10):12181227. DOI: 10.1001/jama.286.10.1218.

[38] Umpierre D, Ribeiro PA, Kramer CK, et al. Physical activity advice only or structured exercise training and association with HbA1c levels in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and metaanalysis[J]. JAMA, 2011,305(17):17901799. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2011.576.

[39] Boulé NG, Kenny GP, Haddad E, et al. Metaanalysis of the effect of structured exercise training on cardiorespiratory fitness in type 2 diabetes mellitus[J]. Diabetologia, 2003, 46 (8):10711081. DOI: 10.1007/s0012500311602.

[40] Pan A, Wang Y, Talaei M, et al. Relation of smoking with total mortality and cardiovascular events among patients with diabetes mellitus: a metaanalysis and systematic review [J]. Circulation, 2015, 132(19): 17951804. DOI: 10.1161 / CIRCULATIONAHA.115.017926.

[41] ŚliwińskaMossoń M, Milnerowicz H. The impact of smoking on the development of diabetes and its complications[J]. Diab Vasc Dis Res, 2017, 14(4): 265276. DOI: 10.1177/1479164117701876.

[42] Zhang Y, Pan XF, Chen J, et al. Combined lifestyle factors and risk of incident type 2 diabetes and prognosis among individuals with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and metaanalysis of prospective cohort studies[J]. Diabetologia, 2020,63(1):2133. DOI: 10.1007/s00125019049859.

[43] Liu G, Li Y, Hu Y, et al. Influence of lifestyle on incident cardiovascular disease and mortality in patients with diabetes mellitus[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2018, 71(25): 28672876. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.04.027.

[44] Tu ZZ, Lu Q, Zhang YB, et al. Associations of combined healthy lifestyle factors with risks of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and mortality among adults with prediabetes: four prospective cohort studies in china, the united kingdom, and the united states [J/OL]. Engineering, 2022[20230220]. https://www. sciencedirect. com / science / article / pii / S2095809922003538.

[45] Liu G, Hu Y, Zong G, et al. Smoking cessation and weight change in relation to cardiovascular disease incidence and mortality in people with type 2 diabetes: a populationbased cohort study[J]. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol, 2020, 8(2): 125133. DOI: 10.1016/S22138587(19)304139.

[46] Lee S, Ng KY, Chin WK. The impact of sleep amount and sleep quality on glycemic control in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and metaanalysis[J]. Sleep Med Rev,2017,31:91101. DOI: 10.1016/j.smrv.2016.02.001.

[47] Han H, Wang Y, Li T, et al. Sleep duration and risks of incident cardiovascular disease and mortality among people with type 2 diabetes[J]. Diabetes Care, 2023,46(1):101110. DOI: 10.2337/dc221127.

[48] Zhang YB, Pan XF, Lu Q, et al. Association of combined healthy lifestyles with cardiovascular disease and mortality of patients with diabetes: an international multicohort study [J]. Mayo Clin Proc, 2023, 98(1): 6074. DOI: 10.1016 / j. mayocp.2022.08.012.

[49] Geng T, Zhu K, Lu Q, et al. Healthy lifestyle behaviors, mediating biomarkers, and risk of microvascular complications among individuals with type 2 diabetes: a cohort study[J]. PLoS Med, 2023, 20(1): e1004135. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1004135.

[50] Zhang YB, Pan XF, Lu Q, et al. Correction to: associations of combined healthy lifestyles with cancer morbidity and mortality among individuals with diabetes: results from five cohort studies in the USA, the UK and China[J]. Diabetologia, 2022, 65(12): 2174. DOI: 10.1007 / s00125022058026.

[51] Liu G, Li Y, Pan A, et al. Adherence to a healthy lifestyle in association with microvascular complications among adults with type 2 diabetes[J]. JAMA Netw Open, 2023, 6(1): e2252239. DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.52239.

[52] Lu Q, Chen J, Li R, et al. Healthy lifestyle, plasma metabolites, and risk of cardiovascular disease among individuals with diabetes[J]. Atherosclerosis, 2023, 367: 4855. DOI: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2022.12.008.

[53] 中国医疗保健国际交流促进会营养与代谢管理分会,中国 营养学会临床营养分会,中华医学会糖尿病学分会,等中国超重/肥胖医学营养治疗指南(2021) [J]. 中国医学前沿杂志 ( 电 子 版), 2021: 13(1): 155. DOI: 10.12037 / YXQY.2021.11-01.

[54] Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation [J]. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser, 2000, 894: 1253.

[55] Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: executive summary. Expert panel on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight in adults[J]. Am J Clin Nutr, 1998,68 (4):899917. DOI: 10.1093/ajcn/68.4.899.

[56] Zhu R, Jalo E, Silvestre MP, et al. Does the Effect of a 3year lifestyle intervention on body weight and cardiometabolic health differ by prediabetes metabolic phenotype? A post hoc analysis of the PREVIEW study[J]. Diabetes Care, 2022, 45 (11):26982708. DOI: 10.2337/dc220549.

[57] Hollander PA, Elbein SC, Hirsch IB, et al. Role of orlistat in the treatment of obese patients with type 2 diabetes. A 1year randomized doubleblind study[J]. Diabetes Care,1998,21(8): 128894. DOI: 10.2337/diacare.21.8.1288.

[58] Miles JM, Leiter L, Hollander P, et al. Effect of orlistat in overweight and obese patients with type 2 diabetes treated with metformin[J]. Diabetes Care, 2002, 25(7): 11231128. DOI: 10.2337/diacare.25.7.1123.

[59] Richelsen B, Tonstad S, Rössner S, et al. Effect of orlistat on weight regain and cardiovascular risk factors following a verylowenergy diet in abdominally obese patients: a 3year randomized, placebocontrolled study[J]. Diabetes Care,2007,30(1):2732. DOI: 10.2337/dc060210.

[60] PiSunyer X, Astrup A, Fujioka K, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of 3.0 mg of liraglutide in weight management [J]. N Engl J Med, 2015, 373(1): 1122.

[61] Wilding JPH, Batterham RL, Calanna S, et al. Onceweekly semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity [J]. N Engl J Med, 2021, 384(11): 9891002.

[62] Apolzan JW, Venditti EM, Edelstein SL, et al. Longterm weight loss with metformin or lifestyle intervention in the diabetes prevention program outcomes study[J]. Ann Intern Med, 2019,170(10):682690. DOI: 10.7326/M181605.

[63] Kohan DE, Fioretto P, Tang W, et al. Longterm study of patients with type 2 diabetes and moderate renal impairment shows that dapagliflozin reduces weight and blood pressure but does not improve glycemic control[J]. Kidney Int, 2014, 85(4):962971. DOI: 10.1038/ki.2013.356.

[64] Wolever TM, Chiasson JL, Josse RG, et al. Small weight loss on longterm acarbose therapy with no change in dietary pattern or nutrient intake of individuals with noninsulindependent diabetes[J]. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord, 1997,21(9):756763. DOI: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800468.

[65] Boraska V, Franklin CS, Floyd JA, et al. A genomewide association study of anorexia nervosa[J]. Mol Psychiatry, 2014,19(10):10851094. DOI: 10.1038/mp.2013.187.

[66] Sjöström L, Peltonen M, Jacobson P, et al. Association of bariatric surgery with longterm remission of type 2 diabetes and with microvascular and macrovascular complications[J]. JAMA, 2014, 311(22): 22972304. DOI: 10.1001 / jama.2014.5988.

[67] Adams TD, Davidson LE, Litwin SE, et al. Weight and Metabolic Outcomes 12 Years after Gastric Bypass[J]. N Engl J Med, 2017, 377(12): 11431155. DOI: 10.1056 / NEJMoa1700459.

[68] 中华医学会糖尿病学分会. 中国2型糖尿病防治指南(2020 年版)[J]. 国际内分泌代谢杂志, 2021, 41(5): 482548.DOI:

10.3760/cma.j.cn1213832021082508063.

[69] Hemmingsen B, GimenezPerez G, Mauricio D, et al. Diet, physical activity or both for prevention or delay of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its associated complications in people at increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2017,12(12):CD003054. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003054.pub4.

[70] Gong Q, Zhang P, Wang J, et al. Changes in mortality in people with IGT before and after the onset of diabetes during the 23year followup of the da qing diabetes prevention study[J]. Diabetes Care, 2016, 39(9): 15501555. DOI: 10.2337/dc160429.

[71] Knowler WC, BarrettConnor E, Fowler SE, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin[J]. N Engl J Med, 2002,346(6):393403. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512.

[72] Lindström J, IlanneParikka P, Peltonen M, et al. Sustained reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes by lifestyle intervention: followup of the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study[J]. Lancet, 2006,368(9548):16731679. DOI: 10.1016/ S01406736(06)697018.

[73] Jonas DE, Crotty K, Yun JDY, et al. Screening for prediabetes and type 2 diabetes mellitus: an evidence review for the U. S. Preventive Services Task Force[M / OL]Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US), 2021. [20230210]. https://www. ncbi. nlm. nih. gov/books/NBK574057.

[74] Tabák AG, Herder C, Rathmann W, et al. Prediabetes: a highrisk state for diabetes development[J]. Lancet, 2012,379 (9833):22792290. DOI: 10.1016/S01406736(12)602839.

[75] Chiasson JL, Josse RG, Gomis R, et al. Acarbose for prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus: the STOPNIDDM randomised trial[J]. Lancet, 2002, 359(9323): 20722077. DOI: 10.1016/S01406736(02)089055.

[76] Holman RR, Coleman RL, Chan J, et al. Effects of acarbose on cardiovascular and diabetes outcomes in patients with coronary heart disease and impaired glucose tolerance (ACE): a randomised, doubleblind, placebocontrolled trial [J]. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol, 2017, 5(11): 877886. DOI: 10.1016/S22138587(17)303091.

[77] Sardu C, Paolisso P, Sacra C, et al. Effects of metformin therapy on coronary endothelial dysfunction in patients with prediabetes with stable angina and nonobstructive coronary artery stenosis: the CODYCE multicenter prospective study [J]. Diabetes Care, 2019, 42(10): 19461955. DOI: 10.2337 / dc182356.

[78] Gerstein HC, Colhoun HM, Dagenais GR, et al. Dulaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes (REWIND): a doubleblind, randomised placebocontrolled trial[J]. Lancet, 2019, 394(10193): 121130. DOI: 10.1016 / S01406736(19)311493.

[79] Marso SP, Bain SC, Consoli A, et al. Semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes[J]. N Engl J Med, 2016, 375(19): 18341844. DOI: 10.1056 / NEJMoa1607141.

[80] Marso SP, Daniels GH, BrownFrandsen K, et al. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes [J]. N Engl J Med, 2016, 375(4): 311322.DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603827.

[81] Cannon CP, Perkovic V, Agarwal R, et al. Evaluating the effects of canagliflozin on cardiovascular and renal events in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease according to baseline HbA1c, including those with HbA1c<7%: results from the CREDENCE trial[J]. Circulation, 2020, 141(5): 407410. DOI: 10.1161 / CIRCULATIONAHA.119.044359.

[82] Heerspink H, Jongs N, Chertow GM, et al. Effect of dapagliflozin on the rate of decline in kidney function in patients with chronic kidney disease with and without type 2 diabetes: a prespecified analysis from the DAPACKD trial [J]. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol, 2021, 9(11): 743754. DOI: 10.1016/S22138587(21)002424.

[83] Jhund PS, Kondo T, Butt JH, et al. Dapagliflozin across the range of ejection fraction in patients with heart failure: a patientlevel, pooled metaanalysis of DAPAHF and DELIVER[J]. Nat Med, 2022, 28(9): 19561964. DOI: 10.1038/s41591022019714.

[84] McMurray J, Solomon SD, Inzucchi SE, et al. Dapagliflozin in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction[J]. N Engl J Med, 2019, 381(21): 19952008. DOI: 10.1056 / NEJMoa1911303.

[85] DeFronzo RA, Tripathy D, Schwenke DC, et al. Pioglitazone for diabetes prevention in impaired glucose tolerance[J]. N Engl J Med, 2011, 364(12): 11041115. DOI: 10.1056 /

NEJMoa1010949.

[86] Saremi A, Schwenke DC, Buchanan TA, et al. Pioglitazone slows progression of atherosclerosis in prediabetes independent of changes in cardiovascular risk factors[J]. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2013, 33(2): 393399. DOI: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300346.

[87] Kernan WN, Viscoli CM, Furie KL, et al. Pioglitazone after ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack [J]. N Engl J Med, 2016, 374(14): 13211331. DOI: 10.1056 / NEJMoa1506930.

[88] De Jong M, Van Der Worp HB, Van Der Graaf Y, et al. Pioglitazone and the secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. A metaanalysis of randomizedcontrolled trials [J]. Cardiovascular diabetology, 2017, 16(1): 134.DOI: 10.1186/ s1293301706174.

[89] Wilcox R, Bousser MG, Betteridge DJ, et al. Effects of pioglitazone in patients with type 2 diabetes with or without previous stroke: results from PROactive (PROspective pioglitAzone Clinical Trial In macroVascular Events 04) [J]. Stroke, 2007, 38(3): 865873. DOI: 10.1161 / 01. STR.0000257974.06317.49.

[90]中国高血压防治指南修订委员会,中国高血压联盟,中华医 学会心血管病学分会高血压专业委员会,等 . 中国高血压 防治指南(2018 年修订版)[J]中国心血管杂志[J]. 2019, 24 (1): 2456.DOI:10.3969/j.issn.10075410.2019.01.002.

[91] Ali MK, Bullard KM, Saydah S, et al. Cardiovascular and renal burdens of prediabetes in the USA: analysis of data from serial crosspal surveys, 19882014[J]. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol, 2018, 6(5): 392403. DOI: 10.1016 / S22138587(18)300275.

[92] Roumie CL, Hung AM, Russell GB, et al. Blood pressure control and the association with diabetes mellitus incidence: results from SPRINT randomized trial[J]. Hypertension, 2020,75(2):331338. DOI: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA. 118.12572.

[93] Bress AP, King JB, Kreider KE, et al. Effect of intensive versus standard blood pressure treatment according to baseline prediabetes status: a post hoc analysis of a randomized trial[J]. Diabetes Care, 2017, 40(10): 14011408. DOI: 10.2337/dc170885.

[94] Tran K, Stedman M, Chang TI. Intensive blood pressure control and diabetes mellitusrelated limb events in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: reanalysis of ACCORD[J]. J Am Heart Assoc, 2021, 10(15): e021407. DOI: 10.1161 / JAHA.121.021407.

[95] ACCORD Study Group, Cushman WC, Evans GW, et al. Effects of intensive bloodpressure control in type 2 diabetes mellitus [J]. N Engl J Med, 2010, 362(17): 15751585.DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001286.

[96] Böhm M, Schumacher H, Teo KK, et al. Cardiovascular outcomes and achieved blood pressure in patients with and without diabetes at high cardiovascular risk[J]. Eur Heart J, 2019,40(25):20322043. DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz149.

[97] Cosentino F, Grant PJ, Aboyans V, et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines on diabetes, prediabetes, and cardiovascular diseases developed in collaboration with the EASD [J]. Eur Heart J, 2020, 41(2): 255323. DOI: 10.1093 / eurheartj / ehz486.

[98] Nazarzadeh M, Bidel Z, Canoy D, et al. Blood pressurelowering and risk of newonset type 2 diabetes: an individual participant data metaanalysis[J]. Lancet, 2021, 398(10313): 18031810. DOI: 10.1016/S01406736(21)019206.

[99] Effects of ramipril on cardiovascular and microvascular outcomes in people with diabetes mellitus: results of the HOPE study and MICROHOPE substudy. Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators [J]. Lancet, 2000, 356(9232):860.

[100] Telmisartan Randomised AssessmeNt Study in ACE iNtolerant subjects with cardiovascular Disease (TRANSCEND) Investigators, Yusuf S, Teo K, et al. Effects of the angiotensinreceptor blocker telmisartan on cardiovascular events in highrisk patients intolerant to

angiotensinconverting enzyme inhibitors: a randomised controlled trial[J]. Lancet, 2008,372(9644):11741183. DOI: 10.1016/S01406736(08)612428.

[101] Mottillo S, Filion KB, Genest J, et al. The metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk a systematic review and metaanalysis[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2010,56(14):11131132. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.05.034.

[102] Bays HE, Jones PH, Orringer CE, et al. National lipid association annual summary of clinical lipidology 2016[J]. J Clin Lipidol, 2016, 10(1 Suppl): S1S43. DOI: 10.1016 / j. jacl.2015.08.002.

[103] 中国胆固醇教育计划(CCEP)工作委员会, 中国医疗保健国 际交流促进会动脉粥样硬化血栓疾病防治分会,中国老年学和老年医学学会心血管病分会,等.中国胆固醇教育计划 调脂治疗降低心血管事件专家建议(2019)[J]. 中华内科杂志 , 2020, 59(1): 1822. DOI: 10.3760 / cma. issn. 05781426. 2020.01.003.

[104] Cholesterol Treatment Trialists′ (CTT) Collaboration, Fulcher J, O′Connell R, et al. Efficacy and safety of LDLlowering therapy among men and women: metaanalysis of individual data from 174,000 participants in 27 randomised trials[J]. Lancet, 2015,385(9976):13971405. DOI: 10.1016/S01406736(14)613684.

[105] Cholesterol Treatment Trialists′ (CTT) Collaboration, Baigent C, Blackwell L, et al. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a metaanalysis of data from 170, 000 participants in 26 randomised trials[J]. Lancet, 2010, 376(9753): 16701681. DOI: 10.1016 / S01406736(10)613505.

[106] Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Keech AC, et al. Evolocumab and clinical outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease [J]. N Engl J Med, 2017,376(18):17131722. DOI: 10.1056/ NEJMoa1615664.

[107] Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, et al. Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes[J]. N Engl J Med, 2015, 372(25): 23872397. DOI: 10.1056 / NEJMoa1410489.

[108] Schwartz GG, Steg PG, Szarek M, et al. Alirocumab and cardiovascular outcomes after acute coronary syndrome[J]. N Engl J Med, 2018, 379(22): 20972107. DOI: 10.1056 / NEJMoa1801174.

[109] Mach F, Baigent C, Catapano AL, et al. 2019 ESC / EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk [J]. Eur Heart J, 2020, 41(1): 111188.DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz455.

[110] Banach M, Penson PE, Vrablik M, et al. Optimal use oflipidlowering therapy after acute coronary syndromes: a position paper endorsed by the international lipid expert panel (ILEP) [J]. Pharmacol Res, 2021, 166: 105499. DOI: 10.1016/j.phrs.2021.105499.

[111] Sever PS, Poulter NR, Dahlöf B, et al. Reduction in cardiovascular events with atorvastatin in 2,532 patients with type 2 diabetes: AngloScandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Triallipidlowering arm (ASCOTLLA) [J]. Diabetes Care, 2005,28(5):11511157. DOI: 10.2337/diacare.28.5.1151.

[112] Ridker PM, Pradhan A, MacFadyen JG, et al. Cardiovascular benefits and diabetes risks of statin therapy in primary prevention: an analysis from the JUPITER trial[J]. Lancet, 2012, 380(9841): 565571. DOI: 10.1016 / S01406736(12) 611908.

[113] Preiss D, Seshasai SR, Welsh P, et al. Risk of incident diabetes with intensivedose compared with moderatedose statin therapy: a metaanalysis[J]. JAMA, 2011, 305(24): 25562564. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2011.860.

[114] Navarese EP, Buffon A, Andreotti F, et al. Metaanalysis of impact of different types and doses of statins on newonset diabetes mellitus[J]. Am J Cardiol, 2013, 111(8): 11231130. DOI: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.12.037.

[115] Hadjiphilippou S, Ray KK. Evolocumab and clinical outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease[J]. J R Coll Physicians Edinb, 2017, 47(2): 153155. DOI: 10.4997 / JRCPE.2017.212.

[116] Szarek M, White HD, Schwartz GG, et al. Alirocumab reduces total nonfatal cardiovascular and fatal events: the ODYSSEY OUTCOMES trial[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2019,73 (4):387396. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.10.039.

[117] Sabatine MS, Leiter LA, Wiviott SD, et al. Cardiovascular safety and efficacy of the PCSK9 inhibitor evolocumab in patients with and without diabetes and the effect of evolocumab on glycaemia and risk of newonset diabetes: a prespecified analysis of the FOURIER randomised controlled trial[J]. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol, 2017, 5(12): 941950. DOI: 10.1016/S22138587(17)303133.

[118] Ray KK, Colhoun HM, Szarek M, et al. Effects of alirocumab on cardiovascular and metabolic outcomes after acute coronary syndrome in patients with or without diabetes: a prespecified analysis of the ODYSSEY OUTCOMES randomised controlled trial[J].

Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol, 2019, 7(8): 618628. DOI: 10.1016 / S22138587(19)301585.

[119] O′Donoghue ML, Giugliano RP, Wiviott SD, et al. Longterm evolocumab in patients with established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease[J]. Circulation, 2022, 146(15): 11091119. DOI: 10.1161 / CIRCULATIONAHA. 122.061620.

[120] Ray KK, Wright RS, Kallend D, et al. Two phase 3 trials of inclisiran in patients with elevated LDL cholesterol[J]. N Engl J Med, 2020, 382(16): 15071519. DOI: 10.1056 / NEJMoa1912387.

[121] Wright RS, Ray KK, Raal FJ, et al. Pooled patientlevel analysis of inclisiran trials in patients with familial hypercholesterolemia or atherosclerosis[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2021, 77(9): 11821193. DOI: 10.1016 / j. jacc. 2020.12.058.

[122] Raal FJ, Kallend D, Ray KK, et al. Inclisiran for thetreatment of heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia[J]. N Engl J Med,2020, 382(16): 15201530. DOI: 10.1056 / NEJMoa1913805.

[123] Krychtiuk KA, Ahrens I, Drexel H, et al. Acute LDLC reduction post ACS: strike early and strike strong: from evidence to clinical practice. A clinical consensus statement of the Association for Acute CardioVascular Care (ACVC), in collaboration with the European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC) and the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Cardiovascular Pharmacotherapy [J]. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care, 2022, 11(12): 939949.DOI: 10.1093/ehjacc/zuac123.

[124] Writing Committee, LloydJones DM, Morris PB, et al. 2022 ACC expert consensus decision pathway on the role of nonstatin therapies for LDLCholesterol lowering in the management of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2022, 80(14): 13661418. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2022.07.006.

[125] Ray KK, Raal FJ, Kallend DG, et al. Inclisiran and cardiovascular events: a patientlevel analysis of phase III trials[J]. Eur Heart J, 2023, 44(2): 129138. DOI: 10.1093 / eurheartj/ehac594.

[126] Triglyceride Coronary Disease Genetics Consortium and Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration, Sarwar N, Sandhu MS, et al. Triglyceridemediated pathways and coronary disease: collaborative analysis of 101 studies[J]. Lancet, 2010, 375(9726): 16341639. DOI: 10.1016 / S01406736(10) 605454.

[127] Das SR, Everett BM, Birtcher KK, et al. 2018 ACC expert consensus decision pathway on novel therapies for cardiovascular risk reduction in patients with type 2 diabetes and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Task Force on Expert Consensus Decision Pathways[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2018,72 (24):32003223. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.09.020.

[128] Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA / ACC / AACVPR/ AAPA / ABC/ ACPM / ADA / AGS/ APhA / ASPC/ NLA / PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/ American Heart Association Task Force on clinical practice guidelines[J]. Circulation, 2019, 139(25): e1082e1143.DOI: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000625.

[129] Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Miller M, et al. Cardiovascular risk reduction with icosapent ethyl for hypertriglyceridemia[J]. N Engl J Med, 2019, 380(1): 1122. DOI: 10.1056 / NEJMoa1812792.

[130] Elam M, Lovato LC, Ginsberg H. Role of fibrates in cardiovascular disease prevention, the ACCORDLipid perspective[J]. Curr Opin Lipidol, 2011, 22(1): 5561. DOI: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e328341a5a8.

[131] Waldeyer C, Makarova N, Zeller T, et al. Lipoprotein(a) and the risk of cardiovascular disease in the European population: results from the BiomarCaRE consortium[J]. Eur Heart J, 2017, 38(32): 24902498. DOI: 10.1093 / eurheartj / ehx166.

[132] Saeed A, Sun W, Agarwala A, et al. Lipoprotein(a) levels and risk of cardiovascular disease events in individuals with diabetes mellitus or prediabetes: the atherosclerosis risk incommunities study[J]. Atherosclerosis, 2019, 282: 5256. DOI: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2018.12.022.

[133] Jin JL, Cao YX, Zhang HW, et al. Lipoprotein(a) and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with coronary artery disease and prediabetes or diabetes[J]. Diabetes Care, 2019, 42(7):13121318. DOI: 10.2337/dc190274.

[134] Zhang Y, Jin JL, Cao YX, et al. Lipoprotein (a) predicts recurrent worse outcomes in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients with prior cardiovascular events: a prospective, observational cohort study[J]. Cardiovasc Diabetol, 2020, 19(1): 111. DOI: 10.1186/s12933020010838.

[135] Alkhalil M. Lipoprotein(a) reduction in persons with cardiovascular disease[J]. N Engl J Med, 2020,382(21):e65. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMc2004861.

[136] 2019阿司匹林在心血管疾病一级预防中的应用中国专家共 识写作组。2019阿司匹林在心血管疾病一级预防中的应用中国专家共识[J/OL]. 中华心血管病杂志(网络版),2019,2: 1000020.(2019⁃08⁃19)[2023⁃01⁃25].http: //www.cvjc.org.cn/ index.php/Column/ columncon/ aticle ⁃id/ 183.DOI:10.3760/ cma.j.issn.2096⁃1588.2019.1000020.

[137] ASCEND Study Collaborative Group, Bowman L, Mafham M, et al. Effects of aspirin for primary prevention in persons with diabetes mellitus[J]. N Engl J Med, 2018, 379(16): 15291539. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1804988.

[138] Lin MH, Lee CH, Lin C, et al. Lowdose aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in diabetic individuals: a metaanalysis of randomized control trials and trial sequential analysis[J]. J Clin Med, 2019,8(5):609.DOI: 10.3390/jcm8050609.

[139] Zheng SL, Roddick AJ. Association of aspirin use for primary prevention with cardiovascular events and bleeding events: a systematic review and metaanalysis[J]. JAMA, 2019,321(3):277287. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2018.20578.

[140] Antithrombotic Trialists′ (ATT) Collaboration, Baigent C, Blackwell L, et al. Aspirin in the primary and secondary prevention of vascular disease: collaborative metaanalysis of individual participant data from randomised trials[J]. Lancet, 2009, 373(9678): 18491860. DOI: 10.1016 / S01406736(09)605031.

[141] Wiviott SD, Braunwald E, Angiolillo DJ, et al. Greater clinical benefit of more intensive oral antiplatelet therapy with prasugrel in patients with diabetes mellitus in the trial to assess improvement in therapeutic outcomes by optimizing platelet inhibition with prasugrelthrombolysis in myocardial infarction 38[J]. Circulation, 2008,118(16):16261636. DOI:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.791061.

[142] Bhatt DL, Bonaca MP, Bansilal S, et al. Reduction in ischemic events with ticagrelor in diabetic patients with prior myocardial infarction in PEGASUSTIMI 54[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2016, 67(23): 27322740. DOI: 10.1016 / j. jacc.2016.03.529.

[143] Bhatt DL, Fox KA, Hacke W, et al. Clopidogrel and aspirin versus aspirin alone for the prevention of atherothrombotic events[J]. N Engl J Med, 2006, 354(16): 17061717. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa060989.

[144] Steg PG, Bhatt DL, Simon T, et al. Ticagrelor in patients with stable coronary disease and diabetes[J]. N Engl J Med, 2019,381(14):13091320. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1908077.

[145] Kang J, Park KW, Lee H, et al. Aspirin versus clopidogrel forlongterm maintenance monotherapy after percutaneous coronary intervention: the HOSTEXAM extended study[J]. Circulation, 2023, 147(2): 108117. DOI: 10.1161 / CIRCULATIONAHA.122.062770.

[146] Bhatt DL, Eikelboom JW, Connolly SJ, et al. Role of combination antiplatelet and anticoagulation therapy in diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease: insights from the COMPASS trial[J]. Circulation, 2020, 141(23): 18411854. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.046448.

[147] Pareek A, Chandurkar N, Naidu K. Empagliflozin and progression of kidney disease in type 2 diabetes[J]. N Engl J Med, 2016,375(18):1800. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMc1611290.

[148] Cooper ME, Perkovic V, McGill JB, et al. Kidney disease end points in a pooled analysis of individual patientlevel data from a large clinical trials program of the dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitor linagliptin in type 2 diabetes[J]. Am J Kidney Dis, 2015, 66(3): 441449. DOI: 10.1053 / j. ajkd.2015.03.024.

[149] Thornton SN, Regnault V, Lacolley P. Liraglutide and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes[J]. N Engl J Med, 2017,377(22):

21962197. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMc1713042.

[150] Williams TC, Stewart E. Semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes[J]. N Engl J Med,

2017,376(9):891. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMc1615712.

[151] Bakris GL, Agarwal R, Anker SD, et al. Effect of finerenone on chronic kidney disease outcomes in type 2 diabetes[J]. N Engl J Med, 2020, 383(23): 22192229. DOI: 10.1056 / NEJMoa2025845.

[152] Pitt B, Filippatos G, Agarwal R, et al. Cardiovascular events with finerenone in kidney disease and type 2 diabetes[J]. N Engl J Med, 2021, 385(24): 22522263. DOI: 10.1056 / NEJMoa2110956.

[153] Heerspink HJ, Desai M, Jardine M, et al. Canagliflozin slows progression of renal function decline independently of glycemic effects[J]. J Am Soc Nephrol, 2017,28(1):368375. DOI: 10.1681/ASN.2016030278.

[154] Guthrie R. Canagliflozin and cardiovascular and renal events in type 2 diabetes [J]. Postgrad Med, 2018, 130(2): 149153. DOI: 10.1080/00325481.2018.1423852.

[155] Zelniker TA, Braunwald E. Cardiac and renal effects of sodiumglucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors in diabetes: JACC stateoftheart review[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2018, 72(15): 18451855. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.06.040.

[156] Liu Y, Li J, Ma J, et al. Corrigendum to "The threshold of the severity of diabetic retinopathy below which intensive glycemic control is beneficial in diabetic patients: estimation using data from large randomized clinical trials" by Yuqi Liu, Juan Li, Jinfang Ma, Nanwei Tong[J]. J Diabetes Res, 2020, 2020:5498528. DOI: 10.1155/2020/5498528.

[157] Egan A, Byrne M. Effects of medical therapies on retinopathy progression in type 2 diabetes[J]. Ir Med J, 2011, 104(2):37.

[158] Chew EY, Davis MD, Danis RP, et al. The effects of medical management on the progression of diabetic retinopathy in persons with type 2 diabetes: the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) eye study[J]. Ophthalmology, 2014, 121(12): 24432451. DOI: 10.1016 / j. ophtha.2014.07.019.

[159] Shi R, Zhao L, Wang F, et al. Effects of lipidlowering agentson diabetic retinopathy: a Metaanalysis and systematic review[J]. Int J Ophthalmol, 2018, 11(2): 287295. DOI: 10.18240/ijo.2018.02.18.

[160] Stehouwer C. Microvascular dysfunction and hyperglycemia: a vicious cycle with widespread consequences[J]. Diabetes, 2018,67(9):17291741. DOI: 10.2337/dbi170044.

[161] Lian F, Wu L, Tian J, et al. The effectiveness and safety of a danshencontaining Chinese herbal medicine for diabetic retinopathy: a randomized, doubleblind, placebocontrolled multicenter clinical trial[J]. J Ethnopharmacol, 2015, 164: 7177. DOI: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.01.048.

[162] Huang W, Bao Q, Jin D, et al. Compound danshen dripping pill for treating nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy: a metaanalysis of 13 randomized controlled trials[J]. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med, 2017,2017:4848076. DOI: 10.1155/2017/4848076.

[163] Writing Committee for the Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network, Gross JG, Glassman AR, et al. Panretinal photocoagulation vs intravitreous ranibizumab for proliferative diabetic retinopathy: a randomized clinical trial [J]. JAMA, 2015, 314(20): 21372146. DOI: 10.1001 / jama.2015.15217.

[164] Sivaprasad S, Prevost AT, Vasconcelos JC, et al. Clinical efficacy of intravitreal aflibercept versus panretinal photocoagulation for best corrected visual acuity in patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy at 52 weeks (CLARITY): a multicentre, singleblinded, randomised, controlled, phase 2b, noninferiority trial[J]. Lancet, 2017, 389(10085): 21932203. DOI: 10.1016 / S01406736(17) 311935.

[165] Elman MJ, Bressler NM, Qin H, et al. Expanded 2year followup of ranibizumab plus prompt or deferred laser or triamcinolone plus prompt laser for diabetic macular edema [J]. Ophthalmology, 2011, 118(4): 609614. DOI: 10.1016 / j. ophtha.2010.12.033.

[166] Mitchell P, Bandello F, SchmidtErfurth U, et al. The RESTORE study: ranibizumab monotherapy or combined with laser versus laser monotherapy for diabetic macular edema[J]. Ophthalmology, 2011, 118(4): 615625. DOI: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.01.031.

[167] 中华医学会眼科学分会眼底病学组, 中国医师协会眼科医师分会眼底病学组. 我国糖尿病视网膜病变临床诊疗指南(2022 年) ——基于循证医学修订 [J]. 中华眼底病杂志, 2023, 39(2): 99124. DOI: 10.3760 / cma. j. cn5114342023011000018.

[168] McMurray JJ, Packer M, Desai AS, et al. Angiotensinneprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure[J]. N Engl J Med, 2014, 371(11): 9931004. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1409077.

[169] Solomon SD, McMurray J, Anand IS, et al. Angiotensinneprilysin inhibition in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction[J]. N Engl J Med, 2019,381(17): 16091620. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1908655.

[170] Banka G, Heidenreich PA, Fonarow GC. Incremental costeffectiveness of guidelinedirected medical therapies for heart failure[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2013,61(13):14401446. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.12.022.

[171] Dasbach EJ, Rich MW, Segal R, et al. The costeffectiveness of losartan versus captopril in patients with symptomatic heart failure[J]. Cardiology, 1999, 91(3): 189194. DOI: 10.1159/000006908.

[172] Glick H, Cook J, Kinosian B, et al. Costs and effects of enalapril therapy in patients with symptomatic heart failure: an economic analysis of the Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction (SOLVD) Treatment Trial[J]. J Card Fail, 1995,1 (5):371380. DOI: 10.1016/s10719164(05)800065.

[173] Paul SD, Kuntz KM, Eagle KA, et al. Costs and effectiveness of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition in patients with congestive heart failure[J]. Arch Intern Med, 1994,154(10):11431149.

[174] Reed SD, Friedman JY, Velazquez EJ, et al. Multinational economic evaluation of valsartan in patients with chronic heart failure: results from the Valsartan Heart Failure Trial (ValHeFT) [J]. Am Heart J, 2004, 148(1): 122128. DOI: 10.1016/j.ahj.2003.12.040.

[175] Shekelle P, Morton S, Atkinson S, et al. Pharmacologic management of heart failure and left ventricular systolic dysfunction: effect in female, black, and diabetic patients, and costeffectiveness[J]. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ), 2003,(82):16.

[176] Tsevat J, Duke D, Goldman L, et al. Costeffectiveness of captopril therapy after myocardial infarction[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol, 1995, 26(4): 914919. DOI: 10.1016 / 07351097(95) 002841.

[177] Glick HA, Orzol SM, Tooley JF, et al. Economic evaluation of the randomized aldactone evaluation study (RALES): treatment of patients with severe heart failure[J]. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther, 2002, 16(1): 5359. DOI: 10.1023 / a: 1015371616135.

[178] Weintraub WS, Zhang Z, Mahoney EM, et al. Costeffectiveness of eplerenone compared with placebo in patients with myocardial infarction complicated by left ventricular dysfunction and heart failure [J]. Circulation, 2005, 111(9): 11061113. DOI: 10.1161 / 01. CIR.0000157146.86758.BC.

[179] Caro JJ, MigliaccioWalle K, O′Brien JA, et al. Economic implications of extendedrelease metoprolol succinate for heart failure in the MERITHF trial: a US perspective of the MERITHF trial[J]. J Card Fail, 2005, 11(9): 647656. DOI: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2005.06.433.

[180] Delea TE, VeraLlonch M, Richner RE, et al. Cost effectiveness of carvedilol for heart failure[J]. Am J Cardiol, 1999,83(6):890896. DOI: 10.1016/s00029149(98)010662.

[181] Gregory D, Udelson JE, Konstam MA. Economic impact of beta blockade in heart failure[J]. Am J Med, 2001,110 Suppl 7A:74S80S. DOI: 10.1016/s00029343(98)003878.

[182] VeraLlonch M, Menzin J, Richner RE, et al. Costeffectiveness results from the US Carvedilol Heart Failure Trials Program[J]. Ann Pharmacother, 2001, 35(78): 846851. DOI: 10.1345/aph.10114.

[183] McMurray J, Solomon SD, Inzucchi SE, et al. Dapagliflozin in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction[J]. N Engl J Med, 2019, 381(21): 19952008. DOI: 10.1056 / NEJMoa1911303.

[184] Jhund PS, Kondo T, Butt JH, et al. Dapagliflozin across the range of ejection fraction in patients with heart failure: a patientlevel, pooled metaanalysis of DAPAHF and DELIVER[J]. Nat Med, 2022, 28(9): 19561964. DOI:

10.1038/s41591022019714.

[185] Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, et al. Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes[J]. N Engl J Med, 2015, 373(22): 21172128. DOI: 10.1056 / NEJMoa1504720.

[186] Neal B, Perkovic V, Mahaffey KW, et al. Canagliflozin and cardiovascular and renal events in type 2 diabetes [J]. N Engl J Med,

2017, 377(7): 644657. DOI: 10.1056 / NEJMoa1611925.

[187] Wiviott SD, Raz I, Bonaca MP, et al. Dapagliflozin and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes [J]. N Engl J Med, 2019, 380(4): 347357.DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1812389.

[188] Lee M, McMurray J, Jhund PS, et al. Response by Lee et al to Letter Regarding Article, "Effect of empagliflozin on left ventricular volumes in patients with type 2 diabetes, or prediabetes, and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (SUGARDMHF)"[J]. Circulation, 2021, 144(3): e40. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.055067.

[189] Filippatos G, Anker SD, Pitt B, et al. Finerenone and heart failure outcomes by kidney function/ albuminuria in chronic

kidney disease and diabetes[J]. JACC Heart Fail, 2022, 10 (11):860870. DOI: 10.1016/j.jchf.2022.07.013.

[190] American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 9. Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment: standards of medical care in diabetes2022[J]. Diabetes Care, 2022,45(Suppl 1):S125S143. DOI: 10.2337/ dc22S009.

[191] Lago RM, Singh PP, Nesto RW. Congestive heart failure and cardiovascular death in patients with prediabetes and type 2 diabetes given thiazolidinediones: a metaanalysis of randomised clinical trials[J]. Lancet, 2007, 370(9593): 11291136. DOI: 10.1016/S01406736(07)615141.

[192] West SD, Nicoll DJ, Stradling JR. Prevalence of obstructive sleep apnoea in men with type 2 diabetes[J]. Thorax, 2006,61

(11):945950. DOI: 10.1136/thx.2005.057745.

[193] Shaw JE, Punjabi NM, Wilding JP, et al. Sleepdisordered breathing and type 2 diabetes: a report from the International Diabetes Federation Taskforce on Epidemiology and Prevention[J]. Diabetes Res Clin Pract, 2008, 81(1): 212. DOI: 10.1016/j.diabres.2008.04.025.

[194] Cusi K, Isaacs S, Barb D, et al. American association of clinical endocrinology clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in primary care and endocrinology clinical settings: cosponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) [J]. Endocr Pract, 2022, 28(5): 528562. DOI: 10.1016/j.eprac.2022.03.010.

[195] Duell PB, Welty FK, Miller M, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and cardiovascular risk: a scientific statement from

the American Heart Association[J]. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2022, 42(6): e168e185. DOI: 10.1161 / ATV.

0000000000000153.

[196] Rinella ME, NeuschwanderTetri BA, Siddiqui MS, et al. AASLD practice guidance on the clinical assessment and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease[J]. Hepatology, 2023, 77(5): 1797-1835. DOI: 10.1097 / HEP. 0000000000000323.

[197] ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, et al. 4. Comprehensive medical evaluation and assessment of comorbidities: standards of care in diabetes2023[J]. Diabetes Care, 2023,46 (Suppl 1):S49S67. DOI: 10.2337/dc23S004.

[198] 中华医学会内分泌学分会, 中华医学会糖尿病学分会中国成人2型糖尿病合并非酒精性脂肪性肝病管理专家共识 [J].中华内分泌代谢杂志, 2021, 37(7): 589598. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.cn3112822021010500016.

[199] Sanyal AJ, Van Natta ML, Clark J, et al. Prospective study of outcomes in adults with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease[J]. N Engl J Med, 2021, 385(17): 15591569. DOI: 10.1056 / NEJMoa2029349.

本网站所有内容来源注明为“梅斯医学”或“MedSci原创”的文字、图片和音视频资料,版权均属于梅斯医学所有。非经授权,任何媒体、网站或个人不得转载,授权转载时须注明来源为“梅斯医学”。其它来源的文章系转载文章,或“梅斯号”自媒体发布的文章,仅系出于传递更多信息之目的,本站仅负责审核内容合规,其内容不代表本站立场,本站不负责内容的准确性和版权。如果存在侵权、或不希望被转载的媒体或个人可与我们联系,我们将立即进行删除处理。

在此留言

学习了

75

实用,专业

89